Processual development vision as a material-discursive tool

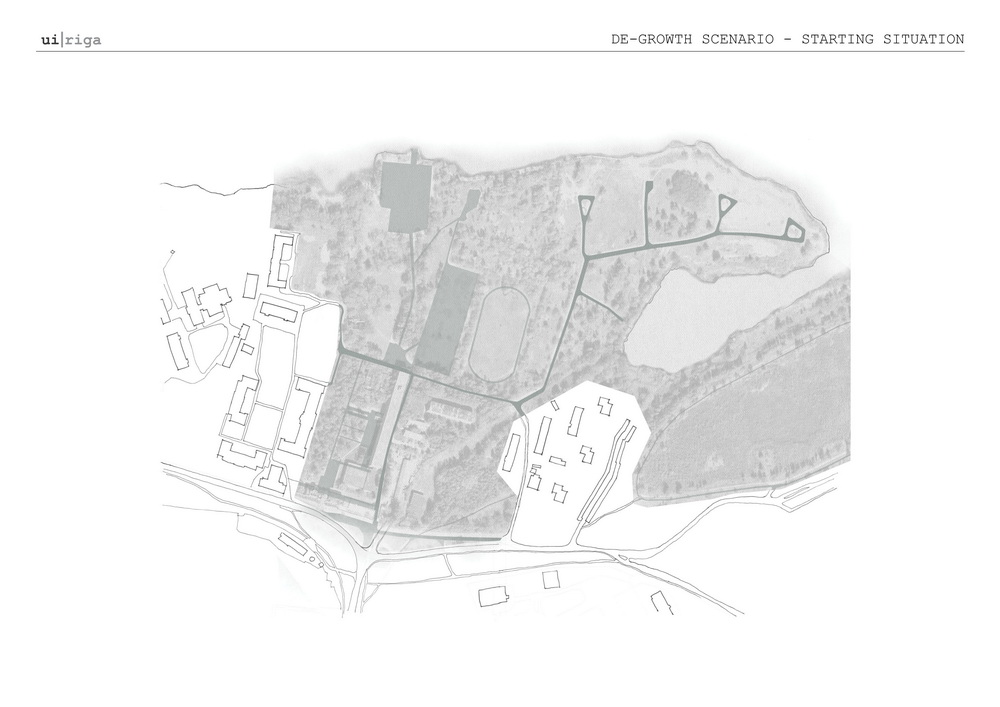

Approaching a disused territory next to Ķīšezers in Čiekurkalns neighbourhood

The city is composed of many overlapping layers – some material, some not – and their juxtaposition defines the city as we know it, not just as physical space but also its cultural, political, and economic processes, all of which together create a distinct framework of possibilities. These layers are not static but ever flowing and changing, continually impacting one another, sometimes making the possibilities difficult to see. Even so, there are places in the city that seem to be blank spots in the collective imagination, where the urban form disintegrates giving way to fragmentation and scarcity of flows. These can be marginal spaces or overlaps where one type of urban logic clashes with another. These can be undeveloped areas or degraded territories in need of revitalisation, and often it is precisely their marginal condition that hinders their transformation. Adding to the complexity, there are many stakeholders involved in city development, and the development itself has varying drivers and executers, be they top-down or bottom-up, privately driven or publicly initiated.

How to develop a vision for the transformation of a marginal territory that would:

- balance public and private interests,

- work across multiple scales,

- respond to contingency over time?

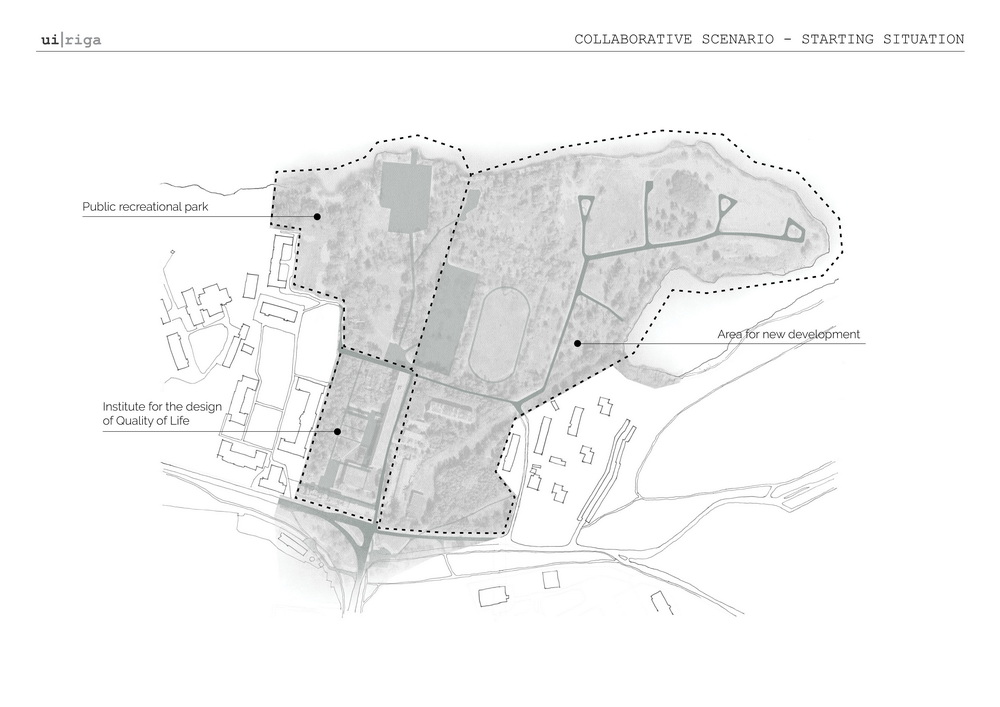

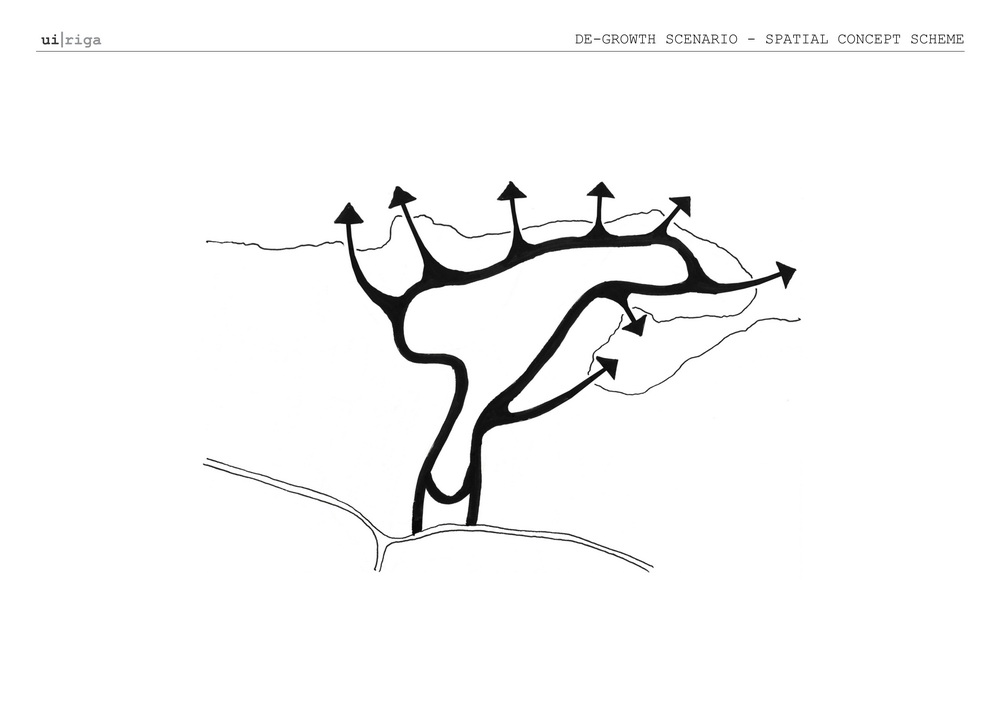

With this approach we aim to undertake a careful investigation of the territory covering multiple scales, in order to enable any intervention to plug gently into the existing. This necessitates working in a non-linear way and covering multiple scales, moving back and forth between them, findings and proposals for one informing those for the others.

This does not mean that each scale could be addressed in exactly the same way, after all, each one provides particular challenges and opportunities. Rather, each scale had to be addressed with specific tools relevant for that particular scale, which could help to gain a better understanding of the territory as a whole. This opens the door to look at and address different kinds of relations, such as those between the building and the courtyard, the courtyard and the lake, the development area and the neighbourhood. The work entails a careful search for what can be done now so that the work does not become redundant if some unforeseen aspect is revealed or there is a shift in existing power relations.

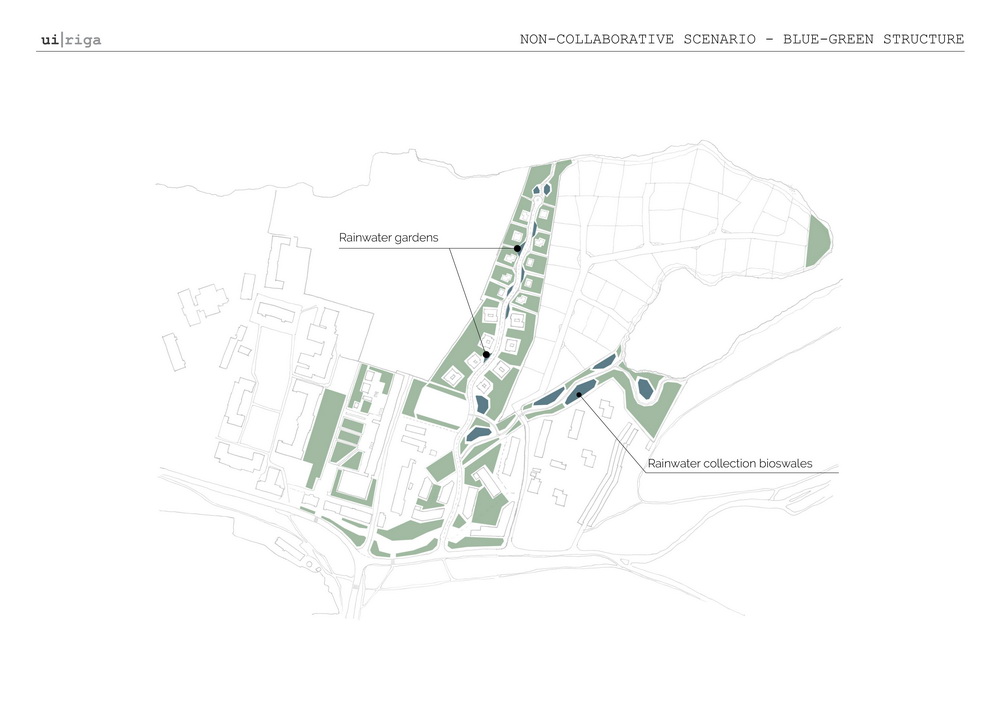

In order to broaden our view beyond the spatial aspects normally prioritised in architectural investigation, we decided to take different types of infrastructure as the basis for our research. Importantly, ‘infrastructure’ here does not entail only underground communications or roads but is viewed more broadly as ‘enablers’. Infrastructure is a valuable point of departure in its capacity to “create conditions and provide possibilities for change without dictating what is going to happen” (Pablo Sendra). This is also how ‘infrastructure’ links the research part of the project and the proposal, which can thus retain an aspect of ambivalence.

All these types of infrastructure form an underlying structure of possibilities from which other, more complex, phenomena can emerge.

By analysing infrastructure networks and the emerging services (or lack thereof) on the neighbourhood scale (L) we are able to identify gaps, which signal what could be necessary for balanced neighbourhood development, or what lacks on the larger scale could local developments address. On the other hand, infrastructure analysis on the local scale (M) enables a close reading of the territory revealing borders, barriers, and obstacles, which need to be addressed to enable productive development that would promote social and material flows. In other words, structuring the research and analysis based on different types of infrastructure respects the existing while revealing gaps, where the energy of intervention could be applied the most effectively.

The conclusions from this first stage of research were synthetised by identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the assemblage and grouping these key points into categories that correspond to the types of infrastructure researched. All future intervention needs to neutralise the threats and actualise the opportunities, while taking into account the strengths and weaknesses of the territory.

A vision for the development of the territory consists of a set of heterogeneous tools, which are applied and revised in their use in a non-linear way.

.

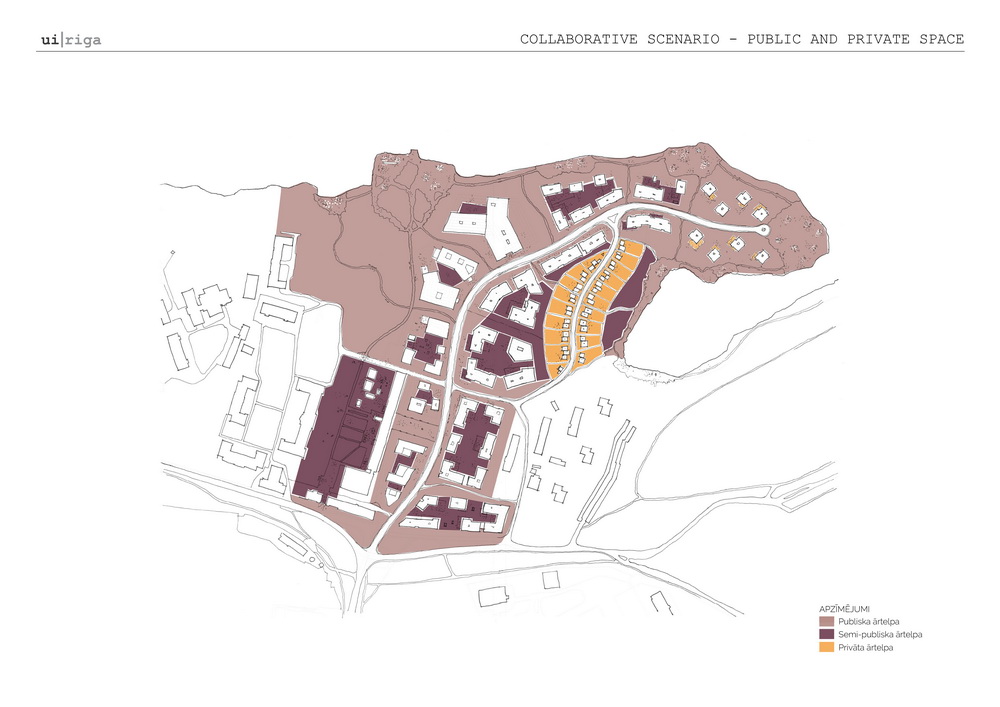

Guidelines for balancing public and private interests

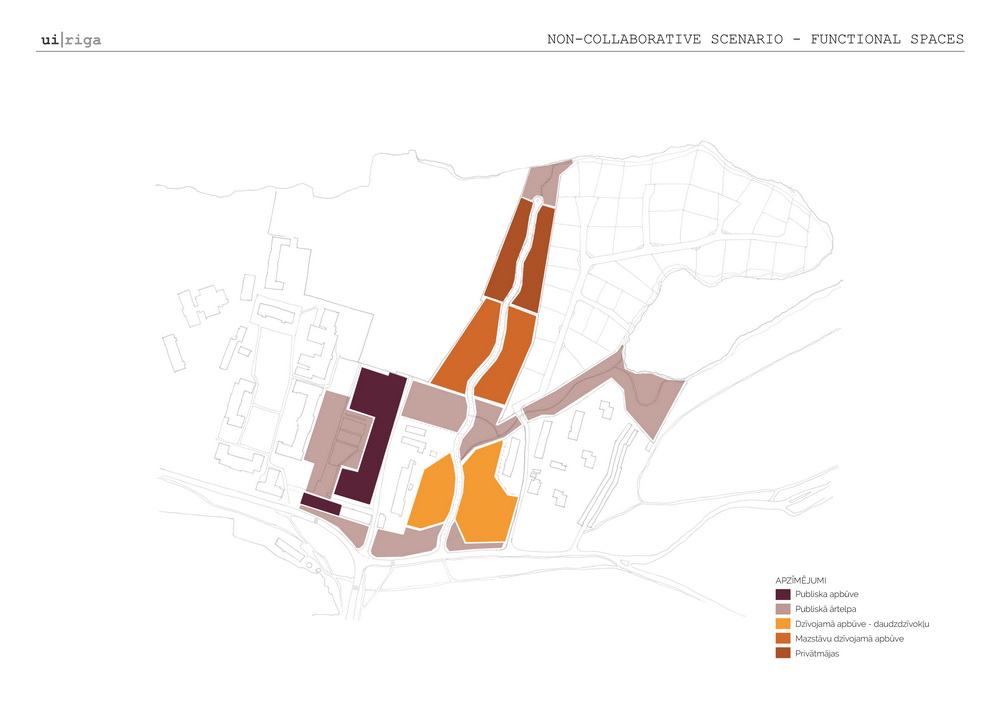

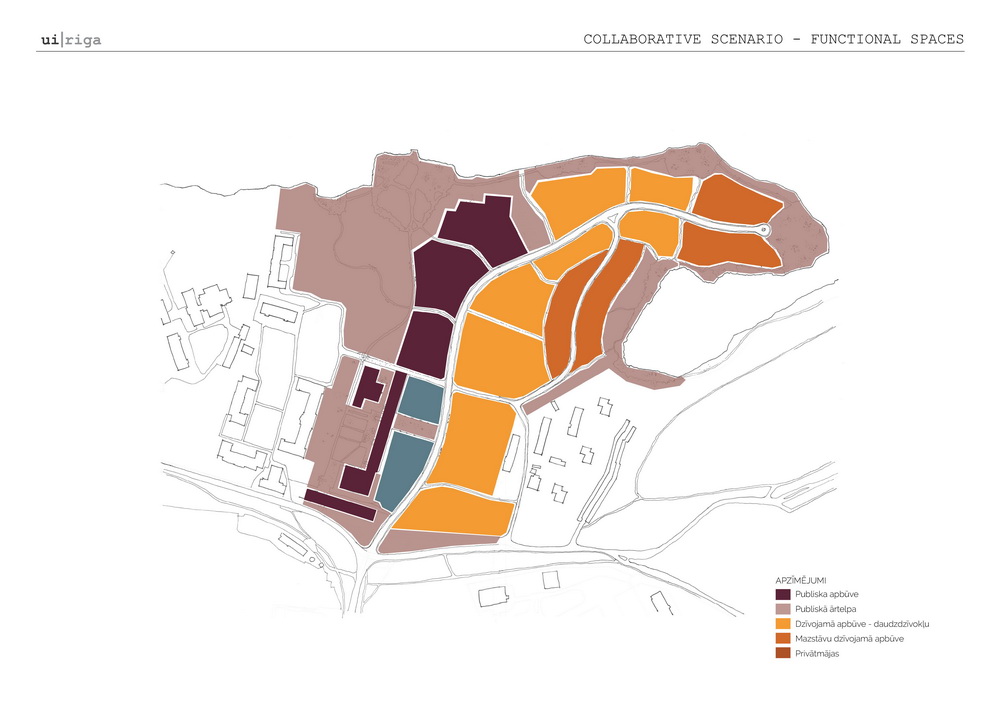

Spatial variety

- Integration of different functions within a development

- Heterogeneous density

- Aesthetic variety

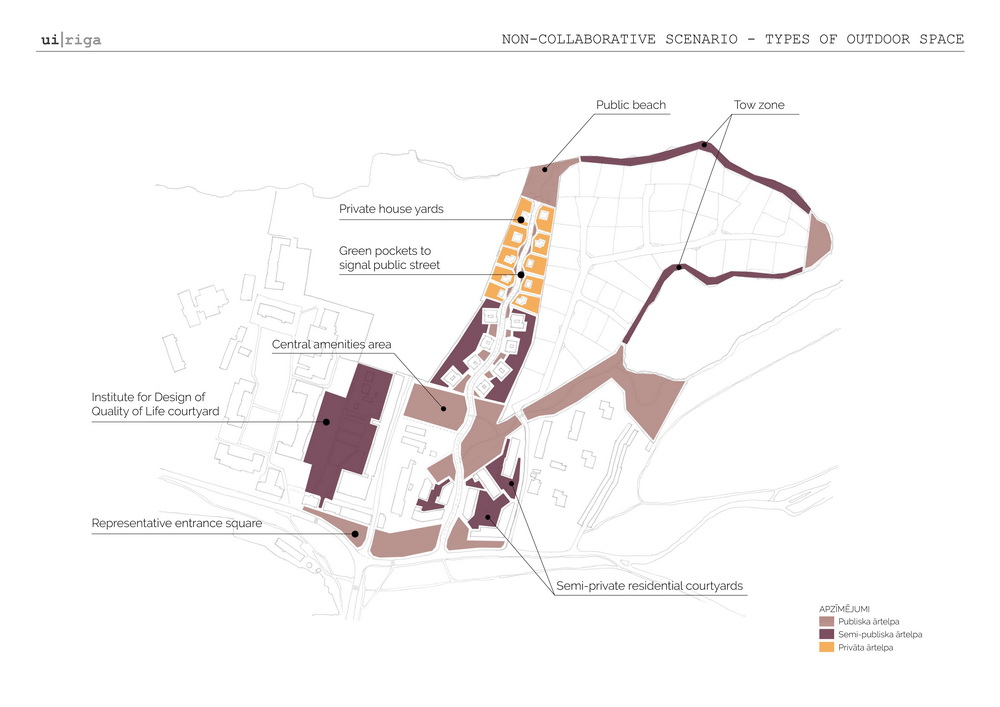

- Various typologies of outdoor space

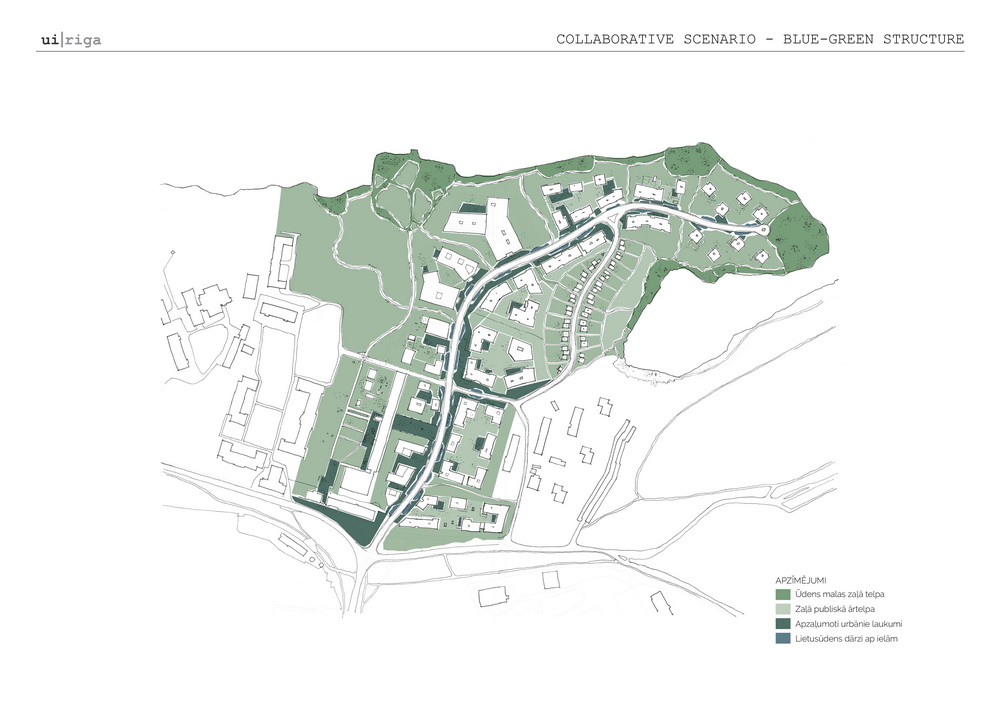

- Preserved and nursed existing natural values

Collaboration

- Community planning

- Collaborative planning tools

- Tools for counteracting gentrification in future development

- Collaboration between different stakeholders and balancing of objectives

Accessibility

- Better connections to the wider neighbourhood

- Access to the lake and public green outdoor space

- Affordable housing

- Amenities for different age groups

- Accessibility to services

The elaboration of development guidelines as one of the tools for the vision comes from a desire to touch all scales, while also acknowledging the complexity of the larger scales and the impossibility of encompassing all of the stakeholders and balancing the whole scope of their needs in one concrete proposal. Instead of trying to provide specific design solutions, the guidelines speak more about how an intervention works and what does it do. Most importantly, the guidelines encompass aspects of development that go beyond the spatial and the physical, touching on social and legal aspects as well. In a way they correspond to general good practice of designing liveable neighbourhoods, while at the same time also being specific to the territory.

While the principal guidelines are public and can be employed by anyone planning, building, or intervening in the territory in any way, whether on a small-scale or a wide sweep, they also help us to develop an urban transformation strategy specifically for the site on the S scale. The main difference and reason, why it was decided to propose a strategy as opposed to a phased master plan, is that, even though both would propose serial spatial interventions in accordance with the guidelines, a strategy can be more flexible and adapt in the face of contingency.

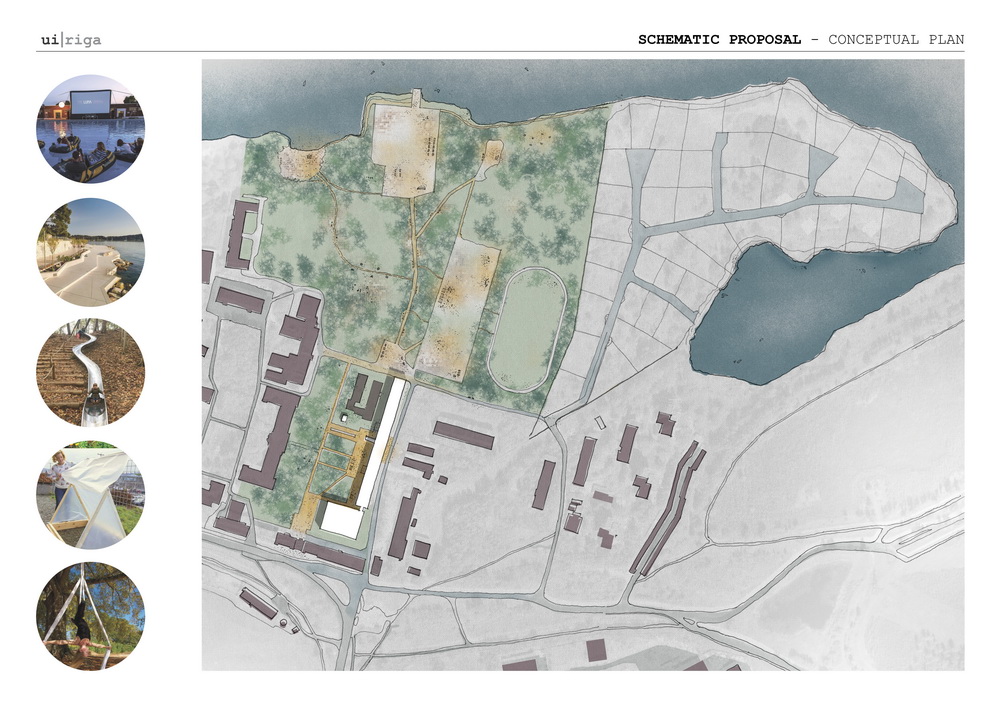

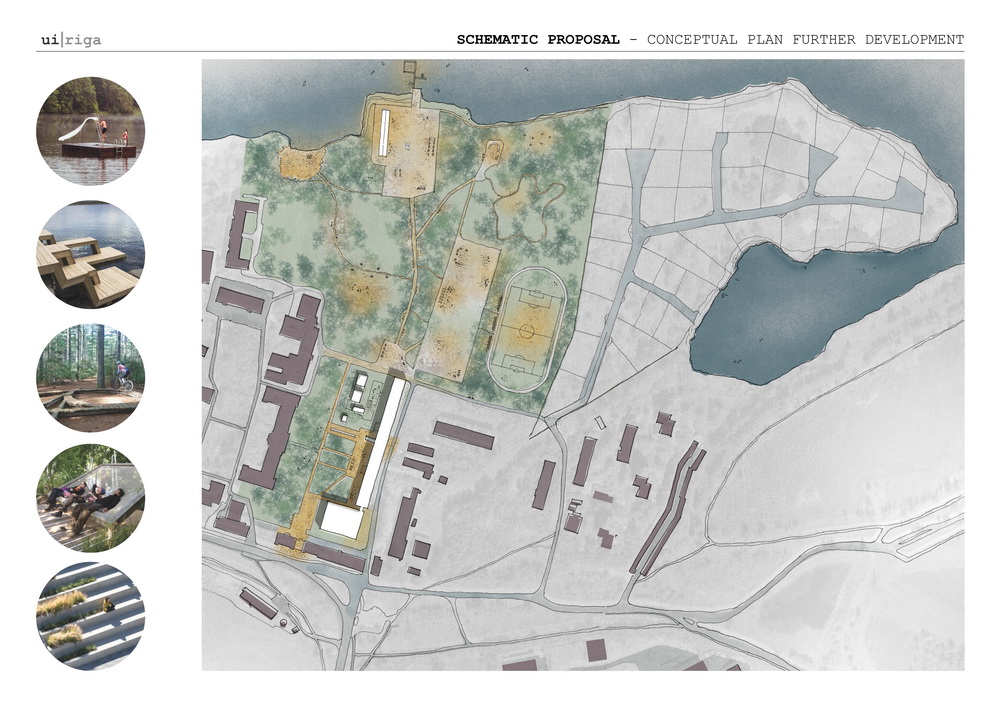

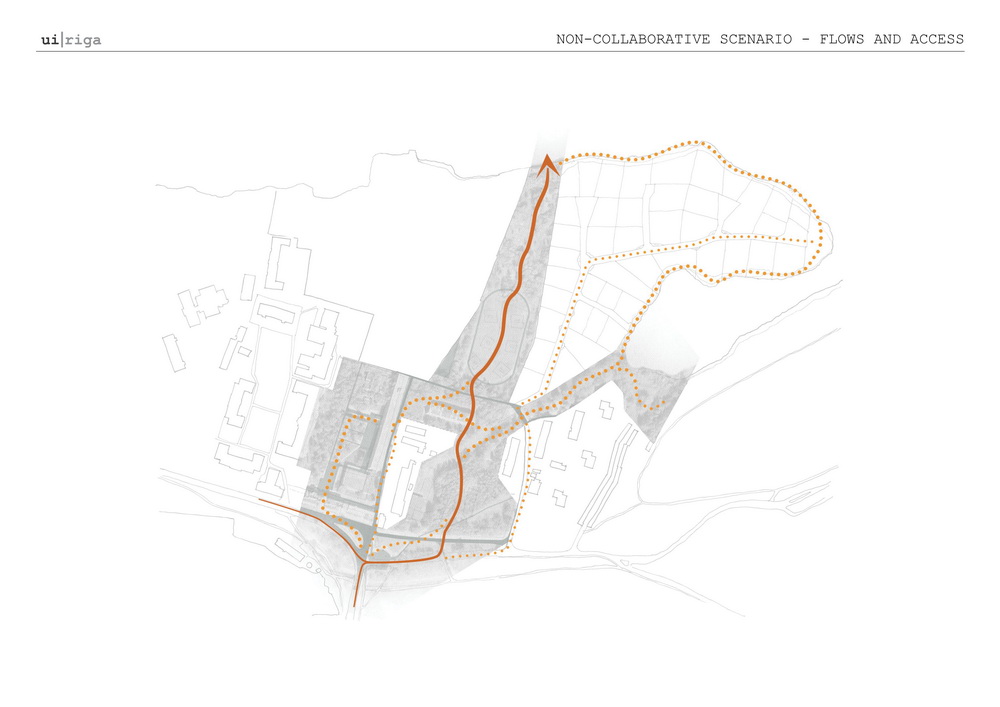

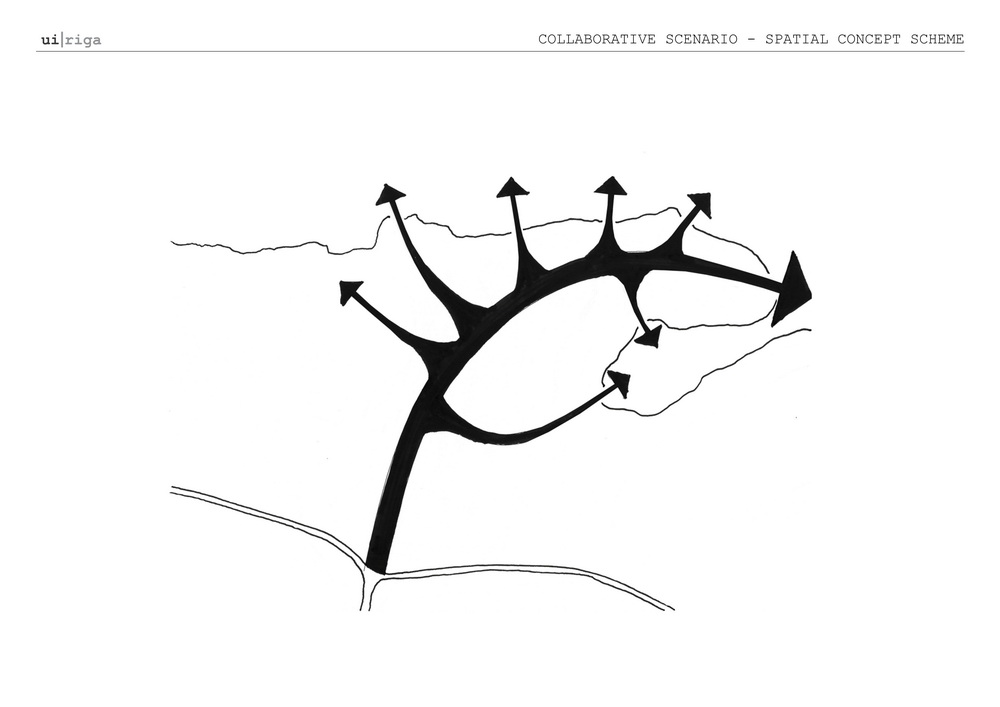

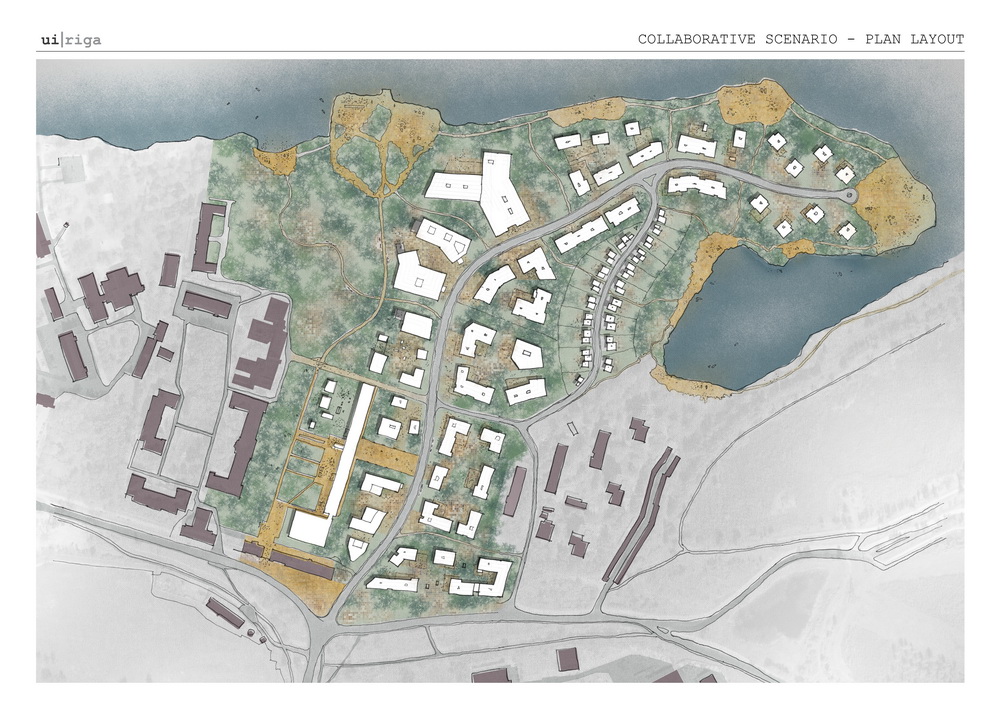

The goal of the strategy is to connect the V36 site to the neighbourhood on the one side and the lake on the other, while enlivening the territory, bringing activity and flows, and creating a much-needed public green space for Čiekurkalns neighbourhood.

A strategy does not finish after the physical intervention on site takes place but requires mechanisms for feedback, adjustment, and revision over time, creating a continuous, contingent process. As the work on site continues, some early possibilities laid out in the strategy are eliminated, while other new ones are revealed. ach intervention merits close observation to see how it works within the assemblage, whether it is absorbed or rejected, and how the whole changes.

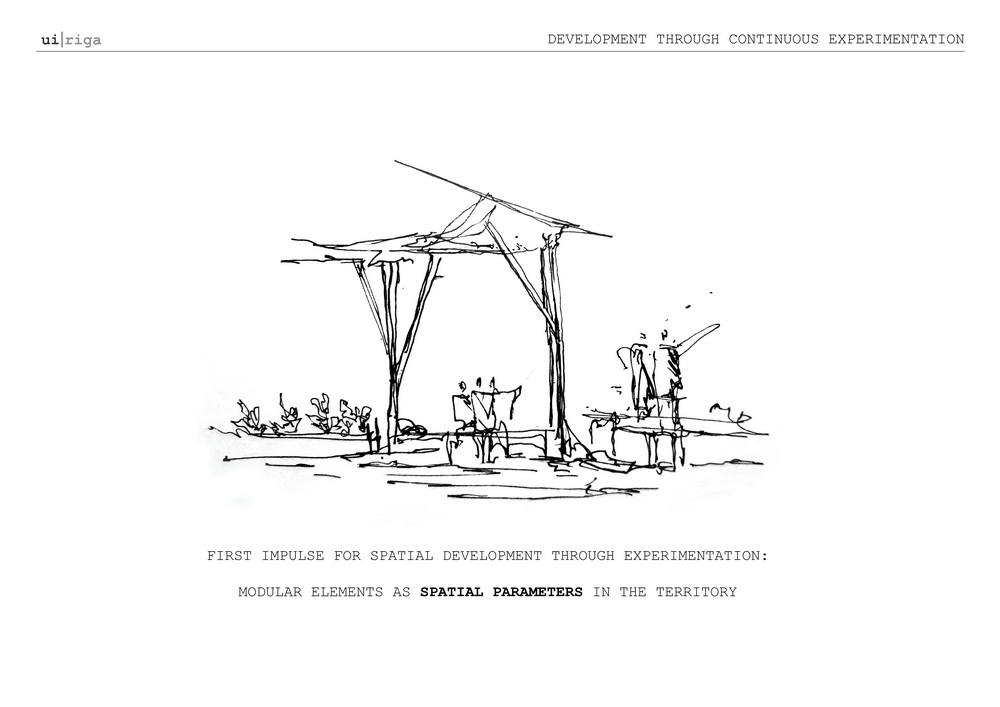

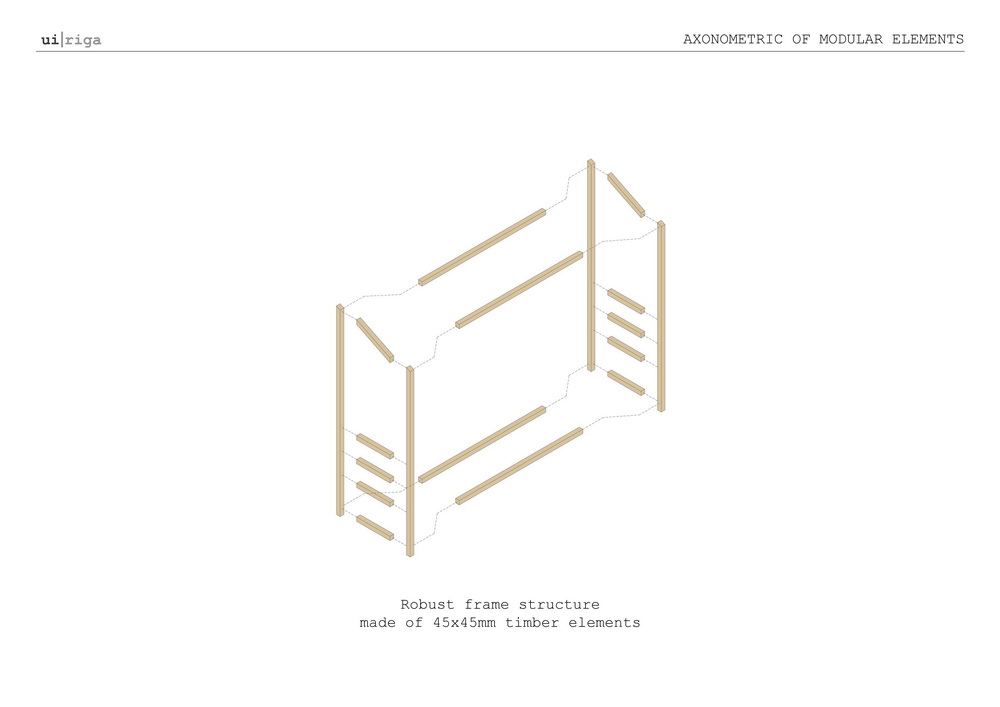

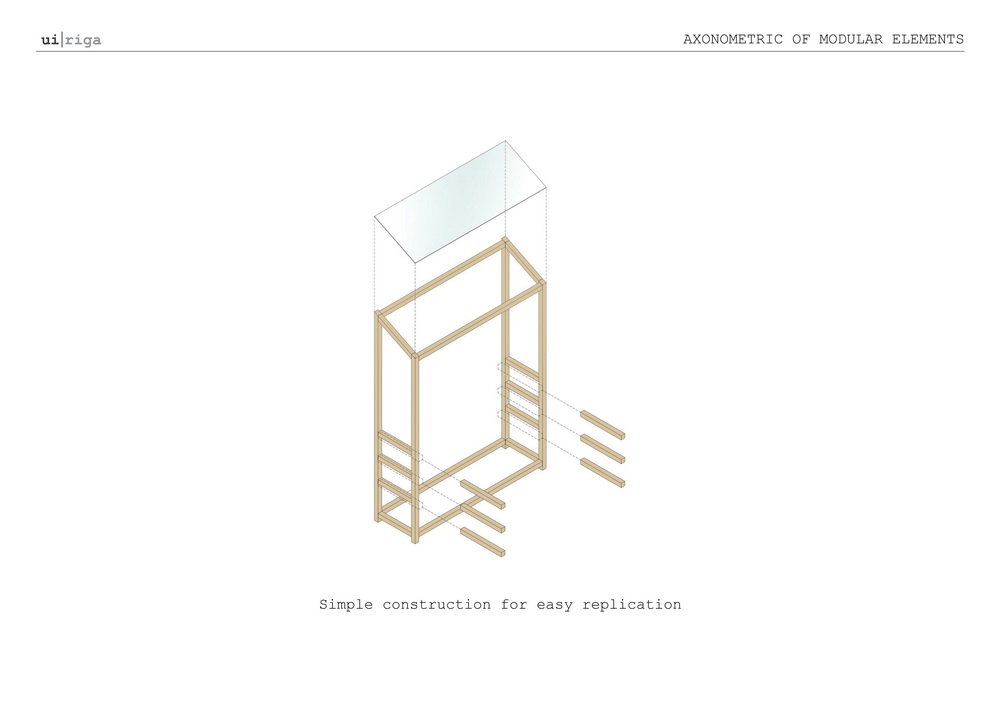

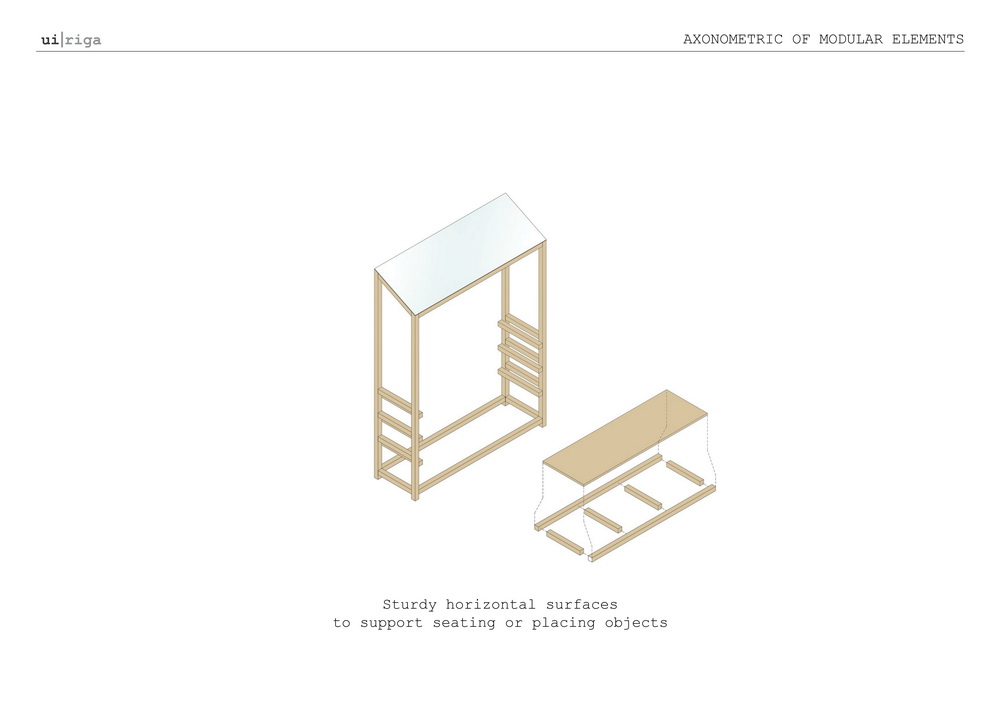

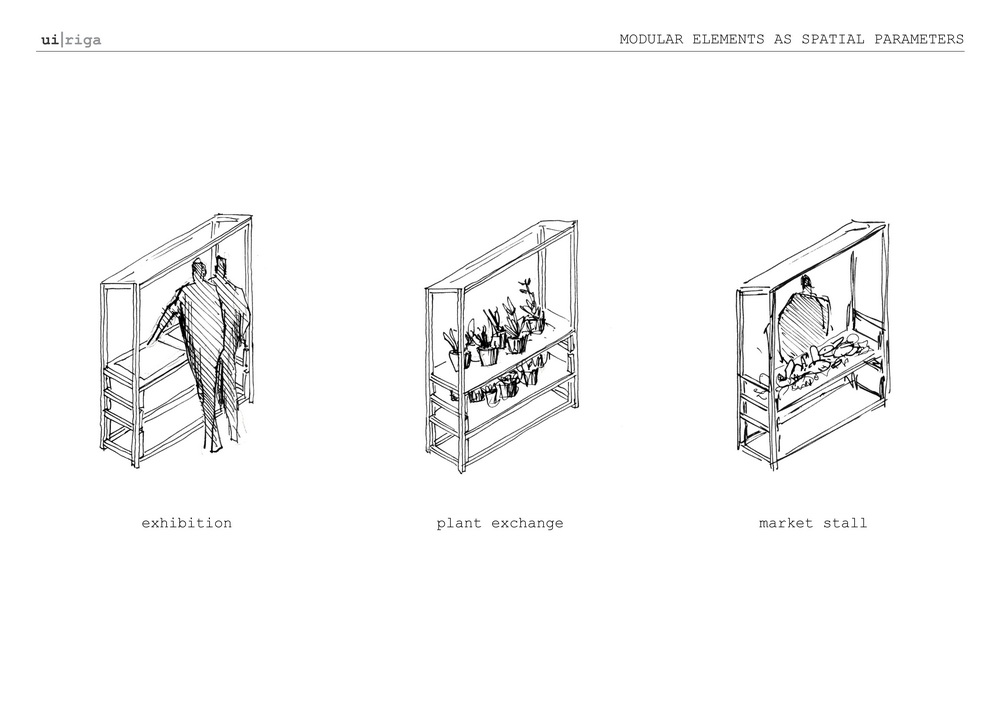

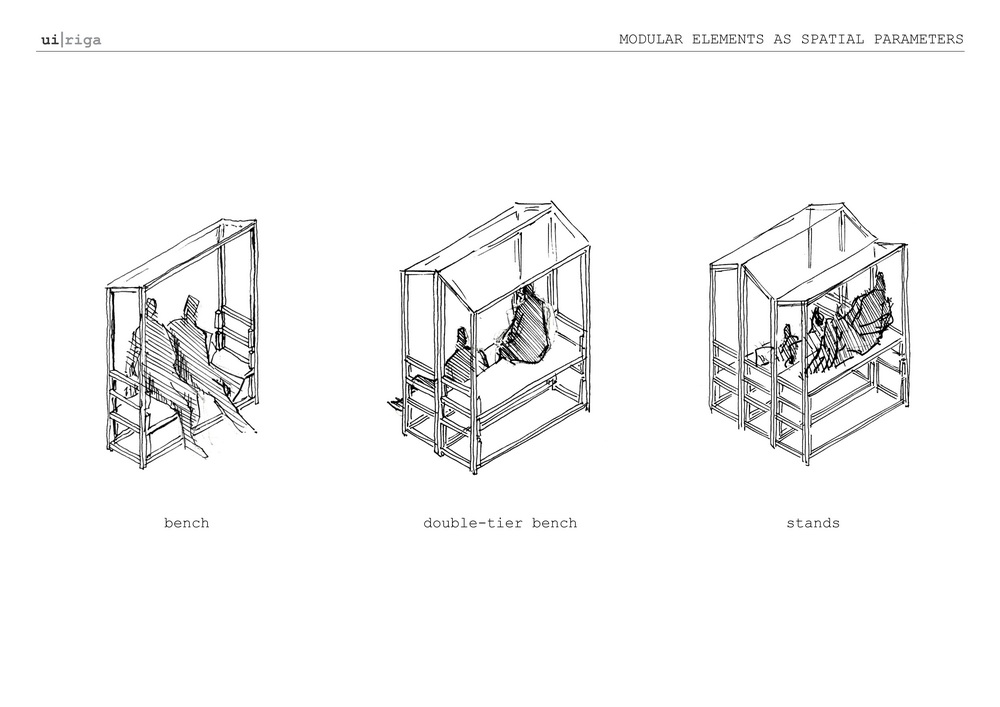

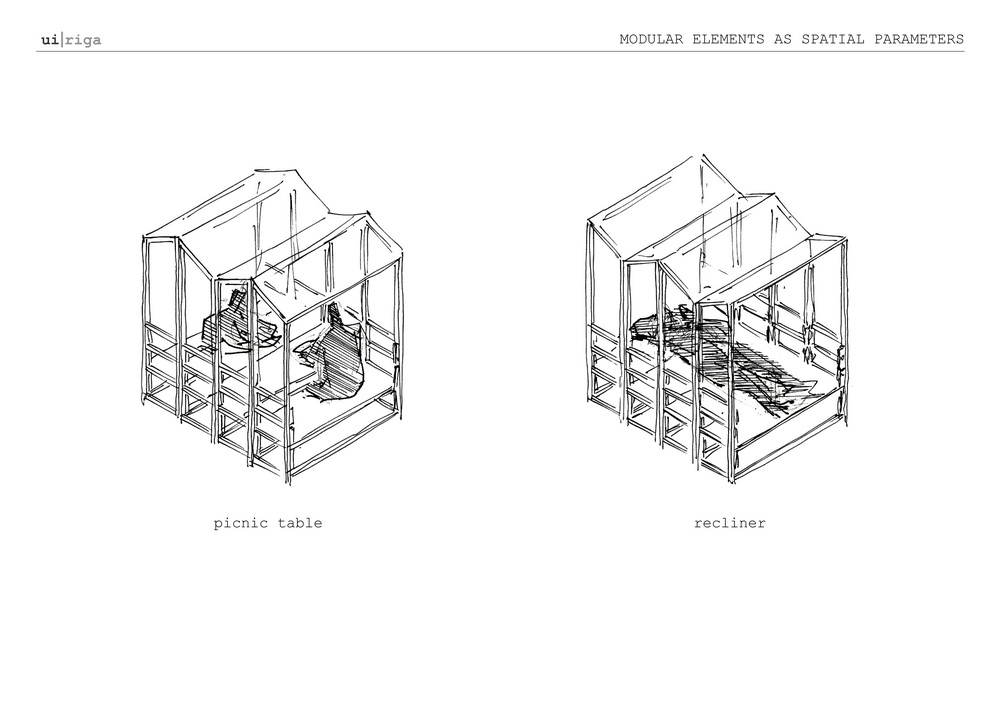

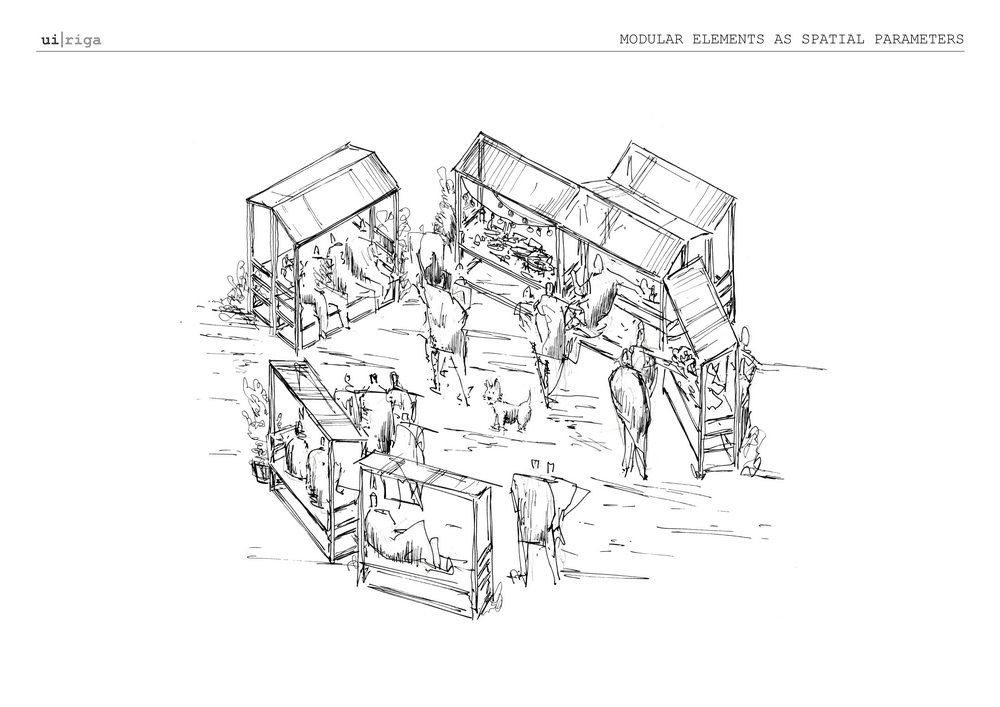

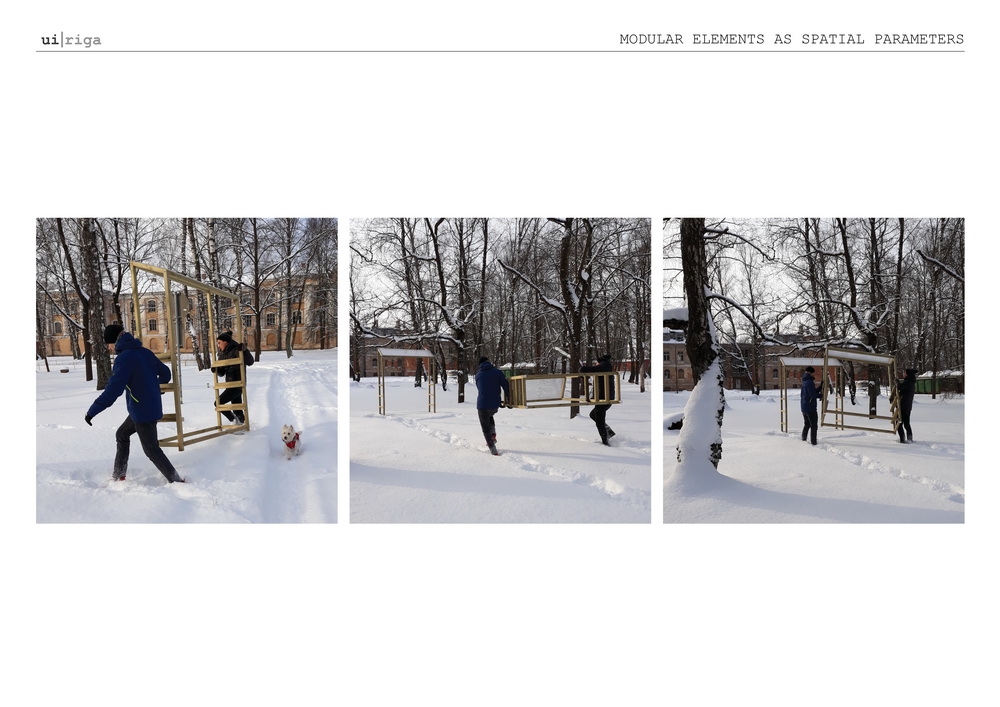

The structures are introduced as disruptions in the territory that trigger new relations and possibilities to actively engage with the environment. Instead of defining and mandating, they encourage discovery and play.

This project was elaborated with the financial support of VKKF, in close collaboration with Free Riga and consulting with Čiekurkalna Attīstības biedrība.

Project creative team:

- Signe Pērkone (architect/urbanist, Urban Institute, ALPS ainavu darbnīca)

- Ramon Cordova Gonzalez (architect/researcher, Urban Institute, MARK arhitekti)

- Arnita Verza (landscape architect, ALPS ainavu darbnīca)

- Džesika Lubāne (community planner, Free Riga)

- Niklāvs Krievs (architect, MARK arhitekti)

- Edijs Matulis (construction)